Cultural Animation

Overview

‘Cultural Animation’ has been pioneered in the UK by the New Vic Theatre through its outreach department, Borderlines. Cultural animation is the process by which Borderlines’ participatory and documentary theatre projects come alive. It puts day to day experiences of ordinary people at the heart of inquiry and in so doing subscribes to the American Pragmatist agenda (Kelemen and Rumens, 2012). The approach has as a starting point the validation of the language used by community members to describe their experiences, and placing the ‘mantle of expert’ upon their shoulders in exploring what changes they would like to see, who should be involved and how to make it happen. By enlisting the creativity and potentiality of the individuals and embracing the historiographies of community members, cultural animation creates opportunities for academics, policy makers and others in relative positions of power to be able to access and understand the ambitions of individuals and communities and create an environment where ‘ordinary people’ can play a role in shaping their world and realising their aspirations and ambitions.

Cultural Animation is a way of working with communities which helps create safe environments in which trusting relations can be established, and where emotions and needs can be expressed openly and potential conflicts revealed and resolved. Culturally animating a community involves acknowledging existing power and knowledge hierarchies and taking steps to minimize them via techniques that build up trusting relationships between participants by inviting them to work together in activities which may be new to them but which draw on their life experiences. These techniques require participants to articulate ideas and experiences in actions and images rather than the written word, consequently dissolving power differentials that may exist within groups.

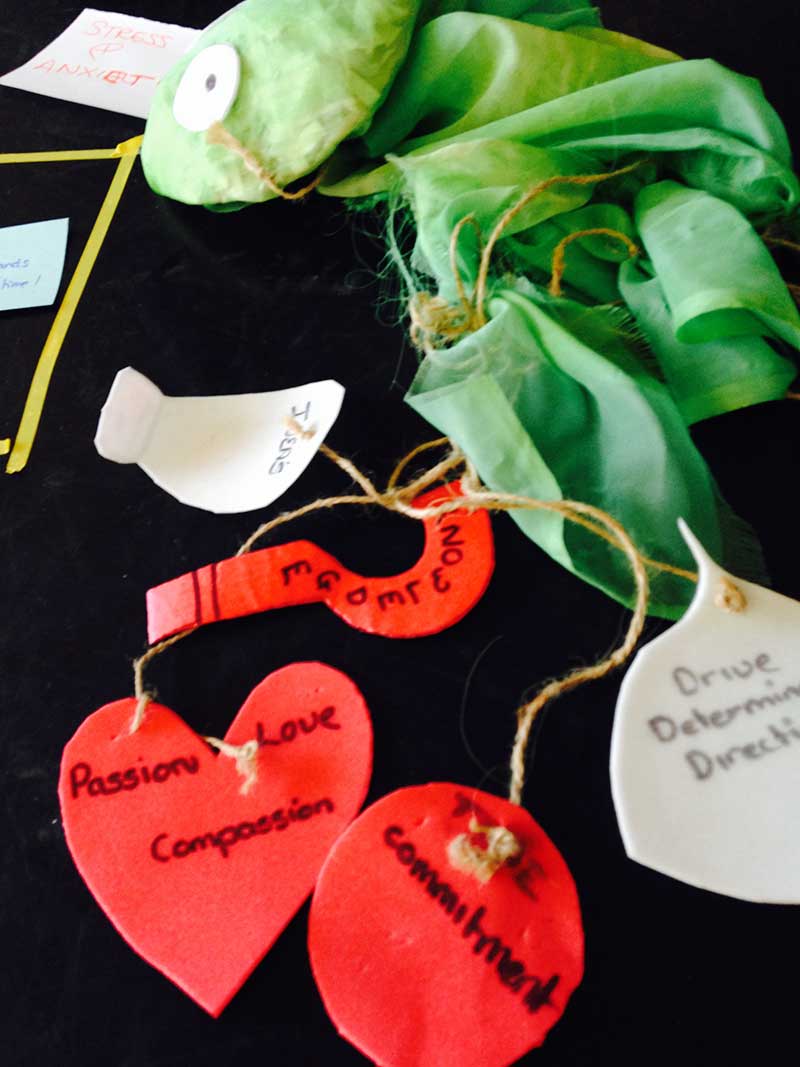

In the process, participants create experiences and artifacts (such as poems, songs, puppets, human tableaux, mini performances and installations, and documentary dramas) that are memorable and energise people around core themes and problems that require solutions. When people make such art together, they engage in different forms of communication, re-define relations between themselves, between ideas and concepts and this allows for new identities to emerge and a sense of community to be formed. Some of the participants describe this process as liberating and as allowing themselves to express the most intimate views about themselves and the world around them. This approach has been used in the projects below:

http://www.keele.ac.uk/bridgingthedivide/

http://www.keele.ac.uk/volunteeringstories/

http://www.keele.ac.uk/exploringpersonalcommunities/

Definition and Approach

The online etymology dictionary defines animation as the “action of imparting life,” from Latin animationem or as “vitality”. As a verb, to animate means “to fill with boldness or courage,” from Latin animatus or to “give breath to”, “to endow with a particular spirit, to give courage to” from anima which in Latin means “life, breath”.

In contemporary use, animation appears to be juxtaposed with ideas of vigor, energy, enthusiasm, ardor, exhilaration, and sprightliness in contrast to staleness or sluggishness. Paul Freire (1994;1996), a Brazilian educator and philosopher sees animation as a form of dialogue which facilitates the development of interpersonal and collective relationships while at the same time helps generate ideas, data and results about things that matter to individuals and communities which sit on the margins of the society. New Vic Borderline’s approach to cultural animation, pioneered in the UK but Sue Moffat, draws on the everyday experiences of ordinary people and their creative abilities to make sense of the world and achieve personal and collective goals by articulating ideas and experiences in actions and images rather than the written word.

Cultural Animation is underpinned by an American Pragmatist philosophy which regards experience as being the starting and ending point of knowing (Kelemen and Rumens, 2013). Rather than being antithetical to knowledge, experience is part of it and contributes to its enhancement. If experience and knowledge are seen as the two sides of the same coin, thinking and acting refer to the same process, namely the process of making our way as best as we can in a universe shot through with contingencies and ambiguities (Menand 2001).

Contexts of its application

One project sought to co-design a health agenda with local communities in Stoke on Trent, in response to the top down health agenda that remains prevalent in public health discourses.

The project explored two related questions and rationales behind the answers:

Could your own local communities make improvements in their own health? (range from “no useful change” to “dramatic change”)

Will your local communities make a difference to their own health in the next 5 years? (range from “only minor changes” to “dramatic change”)

Using a Cultural Animation approach, in the first workshop, we divided the participants in three groups and asked them to develop solutions to three different “problem focussed” community health scenarios using different rules in each group, including the making of different words (such as money, hospital, nurse, doctor, NHS, council) taboo. In the second workshop we created a virtual healthy community for older people. Using the same cultural animation techniques, we co-designed and built virtual communities that enhanced the well-being of older people and identified how such a world would make a difference to the lived experience of people in their communities, and described this difference. The final workshop asked participants to tell the rest of the world including government that how they have created great health in their communities. To achieve this we constructed a three dimensional face book page and twitter account and made theatrical presentations to the Government (which were enacted). We also agreed personal and collective commitments to future work and to maintaining the network, and enumerated and celebrated the assets identified in and by participants and in communities.

The project unearthed a number of assets among which:

- The time and productive engagement of community members, many of whom had no particular input or voice to health sector debates previously.

- Individual and collective creativity, for example musical and poetical talents.

- Access to networks previously unavailable.

- Access to information previously unavailable.

Another project explored communities in crisis in the UK and Japan. The project explored three questions:

- How do communities respond to socio-economic crises or natural disasters?

- What can we learn from communities in crisis?

- How can a Cultural Animation methodology of research can help synergise learning across cultures and across academia and community?

A number of creative outputs ensued from this project:

The ‘Bridging the Gap’ Boat Installation: Journeying from past to future. This interactive audio-visual installation took the participants on an imaginary voyage of self-discovery, inviting them to make artefacts, write poems, record stories about matters that they or their communities might have lost and how that could feed into imagining a different future. The Bridging the Gap Installation was displayed at the Connected Communities Showcase in Edinburgh, 2013 and a podcast was commissioned by the AHRC to capture the complex process by which it had been created and re-enacted. Podcast: ‘Weathering the Storm: How Communities Respond to Adversity’

The Tree of Life Installation. As a symbol of longevity and endurance in Japanese mythology, the ‘Tree of life’ Installation captures stories and artifacts made by Japanese communities affected by the 2011 Tsunami, in experiential workshops led by Sue Moffat, Director of New Vic Borderlines, in Minami Sanriku. The Tree of Life Interactive Installation was showcased at the Connected Communities Festival in Cardiff, 2014.

A third project explored, co-designed and co-performed ‘Untold Stories of Volunteering’. With the help of Cultural Animation techniques, volunteers and related stakeholders were encouraged to articulate their ideas and experiences in actions and images rather than using the spoken word. In Phase 1, this led to the collective production of a series of artefacts, based on themes and issues that were raised by participants in four cultural animation workshops. The artefacts included songs, puppets and models, poetry, shadow puppet theatre, human tableaux and short plays. In Phase 2, we continued to employ the cultural animation methodology whenever we engaged with large groups of volunteers and stakeholders. Thus we conducted a cultural animation workshop with FC United of Manchester and two further workshops with other participants at the New Vic Theatre. The final workshop culturally animated the meanings of legacy, quality and novelty of research within the context of the Connected Communities Programme with a focus on our own project. In broadening the research base beyond Staffordshire, however, we often could not employ cultural animation because of the additional costs involved in getting to a location. We conducted more than 20 interviews around the country with volunteers and volunteer managers from a range of third sector and community based organisations. These included a technology hub, religious charity, arts festival, support organisations and national umbrella groups, as well as individual non-institutional volunteers.

Examples of the cultural animation outputs can be found at: http://www.keele.ac.uk/volunteeringstories/culturalanimationoutcomes/

The resulting documentary drama Untold Stories of Volunteering was performed in three different localities across the UK: New Vic Theatre, Newcastle-under-Lyme; the Richard Attenborough Centre for Disability and the Arts, University of Leicester; and Oxford House Theatre, London. After each show, there was a question and answer session to assess the degree to which the performance resonated or not with the audience’s own experiences of volunteering.

Strengths of cultural animation

- Animates everyday life in a genuine way.

- Builds up trusting relationships between participants by inviting them to work together in activities which may be new to them but which draw on their life experiences.

- Dissolves hierarchies: commonsense, expertise, practical skills are valued in equal measure and each participant contributes to the process according to their own abilities and agendas.

- Rapidly identifies and engages with the yawning gap between “official” plans and strategies for health, and what people actually say they want, and explores new ways of communicating across this gap.

Challenges of cultural animation

- How does one represent in words something that is felt rather than said in words?

- How does one orchestrate multiple voices/acts in an inclusive/democratic way, while assuming the authorial position in writing academic papers?

- How would we assess which situations best suit this approach and how this approach might have been different had public sector people taken part?

- How would we encourage public sector employees to use these techniques in their own engagement strategies?

Reflections on the collaborative work

The strengths and weaknesses of our collaborative projects are closely aligned to the breadth and size of the project group. Academic partners came from diverse disciplines such as management, design, architecture, sociology, communication studies and philosophy. The wide variety of opinions, skills and expertise were a constant source of fresh insights. However at times, it has been difficult to find common ground in order to produce academic papers not only because the academic discourse of each discipline imposed certain rules that were not shared by the other disciplines but also due to the fact that academic and community partners work to different time scales and have different rationales for engaging in community based work.